Tom McAllister’s It All Felt Impossible Explores Growing Up in Philadelphia in 42 Essays

McAllister’s heartfelt and darkly funny new book navigates the ups and downs of being raised in Philly, and the adult who came out the other side.

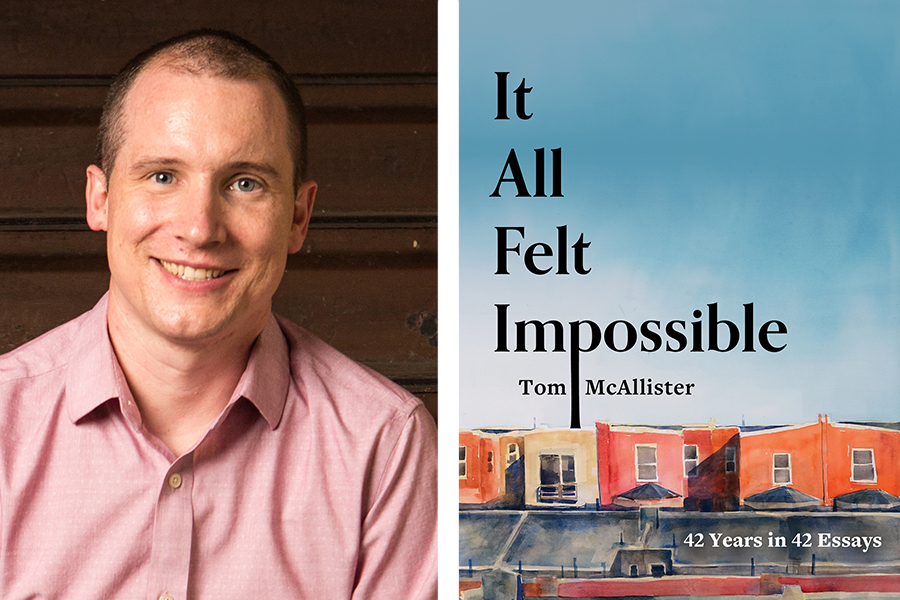

Tom McAllister’s It All Felt Impossible comes out this week. / Author headshot by Matt Godfrey

A few years ago, author and Rutgers-Camden professor Tom McAllister was stuck in a writing rut. In an attempt to extract himself from said rut, he started a project with very specific rules. The main rules: write an essay for every year of his life, and keep the essay lengths to around 1,500 words. The result is It All Felt Impossible: 42 Years in 42 Essays, which comes out this week from Rose Metal Press. The following is an excerpt from the book.

1993

The cool kids in 6th grade had haircuts we called mushrooms: a fade stuck in a bad marriage with a bowl cut. I wanted the same haircut as those guys because girls talked to them and I also wanted to be talked to by girls. My dad took me to Tom & Al’s, a local institution where everyone knew that Al gave good haircuts and Tom did not, a fact I took personally, as if somehow I was accountable for the performance of all Toms everywhere (one of our regular games at recess was listing famous people with our names, and so I had compiled a thorough inventory of all known Toms, both good and bad). People sometimes waited an hour for Al, while Tom sat in his chair reading Playboy. I tried not to be caught peeking at the Playboy. The men around me talked about sports and women and how young people were not as good as they used to be. When a Dr. Dre song came on the radio, one man demanded that Tom turn off the “jungle music.”

I have never in my life had cool hair. The year before, I had mimicked Kevin’s hairstyle and gotten a flattop, a boxy, weird haircut that held its shape when brushed back with a glue stick-like product called Stix Fix. The best-case scenario was to look like Brian Bosworth, and the worst was to look like you had just failed the police exam for the third time. One of the older kids on the bus told me my head looked like a whitewall tire, an insult that made no sense to me then or now, but nonetheless upset me enough that a few days after this, I punched that guy’s younger brother in the back. Later, as a college freshman, I tried to grow my hair out like Jim Morrison’s, but it kept getting thicker and hotter and frizzier (on Instant Messenger, I told a girl I liked that I was growing it out, and the next time she saw me she said, “You look exactly the same”). Now, as more of my forehead reveals itself each year, my main goal is to try not to look disheveled or too old.

My dad didn’t want to wait for Al, so he made me go to Tom. I was too shy to specifically request a mushroom, so I got a blocky and uneven fade instead. I wore a hat every day to hide it — a Pinky and the Brain ballcap my grandmother had bought me. While waiting for the bus, a classmate named Alissa turned to me and asked: “Why do you wear your hat so low?” We rarely spoke to each other, but I’d had a crush on her for as long as I was aware of the possibility of having crushes. I told her I was wearing it that way as a joke, and to prove I didn’t care about my hat at all, I ripped it off and threw it into the bushes and decided never again to wear a hat. There is no way she remembers this conversation. She may not even remember me.

Everything changed, hairwise, in our school when Nick, one of the cool kids showed up with his head shaved. The day before, he and his younger brother had had their bikes stolen by “some kids from Shawmont,” which was one of the public schools nearby, and which we all understood to mean “some Black kids.” There are racists everywhere, but I didn’t realize until I’d lived outside this area how differently it manifests by location; in Philly, it is open and aggressive, whereas in other parts of the country, it’s more subdued and polite, though just as destructive. In grad school, I included the detail about “jungle music” in a short story, and a classmate who had grown up richer than anyone I have ever met said, “I don’t understand — is this story set in, like, the fifties?” Casual racism was part of the atmosphere. Groups of men sat in circles and unhinged their jaws and let all the world’s garbage spew out onto the floor, and then they invited the kids to play in it.

Nick’s father, a Philly cop, was enraged, not at the thieves, but at his sons for having been robbed. He whipped his kids with a belt and then sat them in kitchen chairs and shaved their heads. They both had abrasions on their skulls where he’d shaved too aggressively. He told them, “If you didn’t have those ni—- haircuts you wouldn’t have got robbed,” which was presented to us as a punchline. Because you could still get detention for using that word at school, many guys had turned it around and called each other “Reggin” as a way of sneaking the slur into daily conversation. A guy named Eric had learned this trick from his father, also a cop. This was back when everyone’s mom was a nurse and everyone else’s dad was a cop (my dad did every other possible job at some point: door-to-door sales, mail delivery, restaurants, truck driving, warehouses, computers). I never used the word myself, but I stood there and laughed when everyone else said it, so who cares about me? I laughed at every racist joke, especially the ones I didn’t really comprehend. I was a coward then and I’m often a coward now.

In my first book, I told the story of attending a neighborhood Christmas party in my first year as a homeowner in the Jersey suburbs, standing among a group of men and feeling that change in the atmosphere when one of the guys looked over his shoulder and realized we’re all white here and nobody could yell at him for what he was about to say. He leaned in like a child on the playground telling a joke he’d stolen from his drunk uncle, some gag about monkeys or Obama or African names. Another guy bragged about the tricks he’d used to deter a Black family from buying the house where we now lived. Later, one of these guys pointed at my Honda Civic and asked why I was driving “a Dink car,” a slur I had never even heard before. When I saw one of those neighbors reading my book on his porch, I rushed across the street to reassure him that story was actually about racists in my old neighborhood. “I would hate to think we lived near anyone who thought like that,” he said. But it was him who had made the jokes. He was the racist in the book, and he didn’t even remember it, or he did and he was daring me to call his bluff.

I am trying to get better at interrupting, saying, “I don’t really like this conversation,” or “I think you’ve got this all wrong,” or something. It’s not enough to just not be racist, or to feel bad about it; silence is a tacit approval of everyone else’s racist bullshit. A whole life devoted to avoiding awkwardness is pointless.

Well-meaning people have always pushed the notion that we just have to wait out the racists and watch them die off. The past few years have been a stark reminder of how stupid this idea is, how shortsighted and meaningless, to think the only way to fight racism is to hang around and wait a while. Thanks to Facebook, I know Nick and his brother are Trump supporters and they spend days posting cruel memes about lazy Mexicans and Black thugs. They love the concept of walls, generally, and feel that most liberals should probably be put in jail, just to be safe. One of them has kids and they’ll grow up the same way. It all keeps going.

After Nick and his brother got their heads shaved, everyone else followed. The principal sent a note home to parents addressing concerns that the head shaving was somehow a gang symbol. My mom took me to get my head shaved too. In the middle of the shave, Tom stopped and called her over to say, “Something’s wrong here,” one of the worst statements you can hear from any barber. My head was covered in scaly, peeling skin. Because I was half-shaved the only option was to finish the job and figure out the rest later. Within the space of our two-mile drive home, I convinced myself it was a terminal illness. It all scrubbed off in the shower, which meant it was probably just shampoo I had rubbed into my head without adequately rinsing. I spent the night lying in bed and wishing my hair could grow back, vowing never to cut it again. But hair grows at whatever rate it feels like growing. All I wanted then was to fundamentally change myself, but nothing I tried worked. I was changing all the time, but it was all out of my control.

1997

A couple years after my grandmother’s death, my Uncle Mike fell behind on tax payments and the bank repossessed the house he had inherited from her, the same house in which he’d been raised with my dad and their sister. I knew nothing about his life then; though he took us to occasional Phillies games and once to SummerSlam, I could go months without talking to him. He smoked constantly and had speckled the couch with little burn holes by falling asleep with lit cigarettes in his mouth. He owned a signed Steve Jeltz home run ball and a fist-sized piece of the Berlin Wall, which sat side-by-side on top of a bookshelf. In old photo albums there are pictures of him at one of my birthday parties with a black eye; I later was told that he’d been attacked outside a bar the night before because he was gay (I can’t say anything for sure about his sexual orientation, but this is the commonly accepted explanation in my family). I didn’t know until much later that he’d struggled with drug and alcohol addiction. He’s still alive and on Facebook — he’s been sober a while and works for a church in North Philly — but we haven’t spoken since my dad’s funeral 21 years ago. I never had a sense of how my dad felt about his own brother, besides being frustrated with him. He’d waited too long to ask for help, and now we had one weekend to clear out a three-story home that had been overstuffed with five decades worth of clutter.

I have never worked harder in my life, nor for so little reward. We put in 14-hour days, hauling bag after bag after bag of trash to the local landfill. The dump was open to the public then. You could drive in and drop your trash in the pile, no questions asked. There was a time when you could throw your garbage directly into the incinerator, until the city realized it might be hazardous to have thousands of pounds of toxic ash festering in the middle of our neighborhood. I learned more about the ash pile years later, when I was digging through Philadelphia Inquirer archives for an unrelated project. That ash spent more than a decade on a barge called The Khian Sea until finally it was illegally dumped in Haiti. Incinerated scraps of cloth, boxes of books, thousands of empty beer bottles, splintered drawers and end tables. Whatever it used to be, it was all just garbage. Still, nobody will take responsibility for it. Eventually, even our trash colonizes the developing world.

Between this grueling weekend and LauraBeth’s own experiences sorting through the detritus of her deceased parents’ lives, we both have developed an intense aversion to surrounding ourselves with clutter and leaving it for others to collect and categorize and throw into dumpsters. Once a year we work through our house and eliminate all the excess junk, and despite our vigilance, we still have 10 bags of trash to haul to the curb and two carloads of odds and ends to deliver to Goodwill. I don’t know where it all comes from, the junk. It reproduces on its own and tries to fill every square foot of your home. We manage it with baskets and shelves and in-drawer organizers, and when they overflow, we go to The Container Store for contraptions to hold our baskets. Half of what we donate ends up in a dumpster before anyone has a chance to buy it, and somehow it all ends up adhering to the garbage island in the Pacific Ocean. Eventually, your things find their way back to their own kind, clumping and floating like the 8th continent, this grim new ecosystem of plastic bottles and knickknacks and other objects that used to be treasured by people who were alive.

My dad showed me the room where his sister Molly used to sleep. She’d had a seizure one night when she was 30 and died in her bed. I had only met her as a baby, but I heard about her often enough to know her premature death had scarred everyone in that family in ways I will never fully fathom. Kevin has some memories of her; given our age difference, he has access to a trove of family stories that are all abstractions to me. My dad very rarely spoke about his sister, and when my Uncle Mike did, he struggled not to cry. When their mother was getting older, she sometimes called my mom Molly, and nobody corrected her because it was obviously a term of endearment. Most of her belongings were still in the same place as the day she died. We dumped the contents of her drawers into trash bags and then we dragged the furniture down a winding staircase and then dropped it on the curb for a junk man to find.

My uncle had two friends helping, younger Black men I’d never met before. One wore a t-shirt stylized to look like a Wheaties box, except it said WEEDIES and had an image of a Rasta man smoking a joint on the front. The other owned a dog named Satan. Later, my uncle would have a falling out with Satan’s owner; without any evidence, I had always assumed it was somehow about gambling debts. Uncle Mike would describe this man and Satan as his enemies and tell me not to trust anything they said. I couldn’t imagine a scenario where I would run into Satan or his owner. This isn’t metaphor. It was just a dog’s name.

When I was older, my mom would strongly imply that the man in the WEEDIES shirt was my uncle’s boyfriend. Until the end of high school, I had never knowingly associated with a gay person, and I had no understanding then of the difficulty of growing up closeted in a devoutly Catholic household. On top of that, dating a Black man in our racist little neighborhood — it was beyond my comprehension, beyond my effort.

Recently, my uncle sent me a direct message on Facebook. It had been sitting there a couple weeks before I noticed. It began, “I just read your book,” meaning my memoir. In that book, I describe him as a drunk and a loser, unreliable and dishonest and self-destructive; his role in the book is to be a contrast to my deceased father, and also to process my own worries about being the Bad Brother in contrast to Kevin’s Good Brother. I don’t know if I was being unfair to him. I was so angry still, about everything. His note was a long one, long enough I had to scroll down to skim to the end. I saw numerous words in caps (NEVER and NO ONE and I DIDN’T and YOU LIED), which was enough for me to get the gist. He felt betrayed. I did betray him in the sense that I never tried to know him. At the end of my dad’s funeral, he asked for the printed copy of my eulogy; I wonder if it’s still in his possession. I wonder if he tells his church group about his cold-hearted and ungrateful nephew. When he dies, I won’t know about it for weeks.

By the end of that weekend, we had emptied the house, and only when we sat on the front stoop eating cheesesteaks — the most satisfying meal of my life, considering my exhaustion — did I realize how sad my dad was. He clapped his hand on my shoulder and told me he loved me — not unusual for him, but for a brief moment, I felt his full weight on me, as if I was the only thing keeping him on his feet. The house he’d grown up in was gone. His brother was never going to become the person my dad wished he could be. I was 15 and convinced that I understood the world better than anyone. I’ve tried to bury that arrogant, narrow-minded version of me, but some days I want to resurrect him. I want to cling to that defiance, and that confidence. It never felt good, exactly, but it felt like a direction.