How Surfside Took Over the Cocktail World

In just three short years, the canned vodka and iced tea cocktail from Kensington’s Stateside Distillery went from unknown to the fastest-growing alcohol brand in the country. But what happens when the buzz wears off?

Riding the undeniable wave of Surfside / Photo-illustration by Andre Rucker

It’s moving day at Surfside headquarters in Kensington.

In the main office upstairs, cardboard boxes sit ready to be taped closed, and the neon “Surfside” light has been taken down from the exposed brick wall. The mini fridge is still there, and so are the low-slung couch and conference table, where employees of the canned cocktail brand and its sister company, the award-winning Stateside vodka, met to hash out ideas. A half-erased whiteboard on the wall bears remnants of the last team meeting: a list of potential colleges to pursue for partnerships, a crude sketch of a marketing idea (maybe a raised platform for branded photo ops at music festivals?), and the words “No Bubbles, No Troubles” (a hashtag they use to collect photos of customers with their Surfside cans; they’re up to more than 4,000 submissions).

It’s quiet here; most of the company’s 227 employees have already relocated to the new office, a 10,000-square-foot building in Trevose. The move is only temporary, though, a quick pivot from the original plan, which was to combine the company’s corporate offices, distribution, and distillery under one (massive) roof in Northeast Philly. Stateside’s owners — two pairs of brothers, Clement and Zach Pappas and Matt and Bryan Quigley — signed a long-term industrial lease on the property and broke ground two years ago. Their new headquarters would be 40,000 square feet. It would have double-decker office space. It would increase their operations space by 900 percent. More parking spots, and more room to make their Stateside vodka, which they launched in 2015, and their Stateside canned vodka-soda drinks, rolled out in 2021.

More room, also, for Surfside. They’d launched the line — canned vodka mixed with flavors of tea and lemonade, 4.5 percent ABV, 100 calories — in early 2022, and it was an instant success. But the success was still manageable, certainly nothing that wouldn’t fit in 40,000 square feet.

Surfside on the beach / Photograph by Claudia Gavin

A year after signing the lease, they realized their mistake. Construction on the new place had barely started, and already they’d outgrown it. Because Surfside wasn’t just a success.

It was wildfire.

The numbers lay it out starkly, undeniably, incredibly: In its first year, Surfside produced a modest 200,000 cases; the next year, sales grew to 1.3 million cases. In 2024, only two years after Surfside launched its iced tea (its other flagship flavors — peach tea, half tea and half lemonade, and lemonade — were released in early 2023), that number skyrocketed to just over 4.9 million. Distribution spread, too, from seven states at the beginning of 2023 to all 50 states now — plus St. Thomas, the Bahamas, and Grand Cayman. (Coming soon: Antigua and Honduras.) In 2024, Surfside was the fastest-growing alcohol brand in the United States, with a whopping 378 percent annual growth. If you break that math down, Surfside sold about nine cases a minute last year.

So, yeah. Forty thousand square feet isn’t going to cut it.

They’re still going to build out the property as a warehouse and distribution center, Matt Quigley, 41, tells me as he walks me from the upstairs office to the Stateside Vodka Bar, an industrial-looking space that serves up the brand’s signature cocktails and canned products. A glass wall separates the bar from the distillery floor, where a large, shiny, custom copper still stands rather majestically.

It’s a far cry from Quigley’s first still, which he and Bryan found on eBay back in 2013: a “legally dubious” repurposed beer keg welded to high school lab equipment. The brothers, then in their 20s, Googled the basics of distilling and secretly set up shop in their parents’ basement in Fort Washington. Matt Quigley pulls the rusty contraption out from a corner.

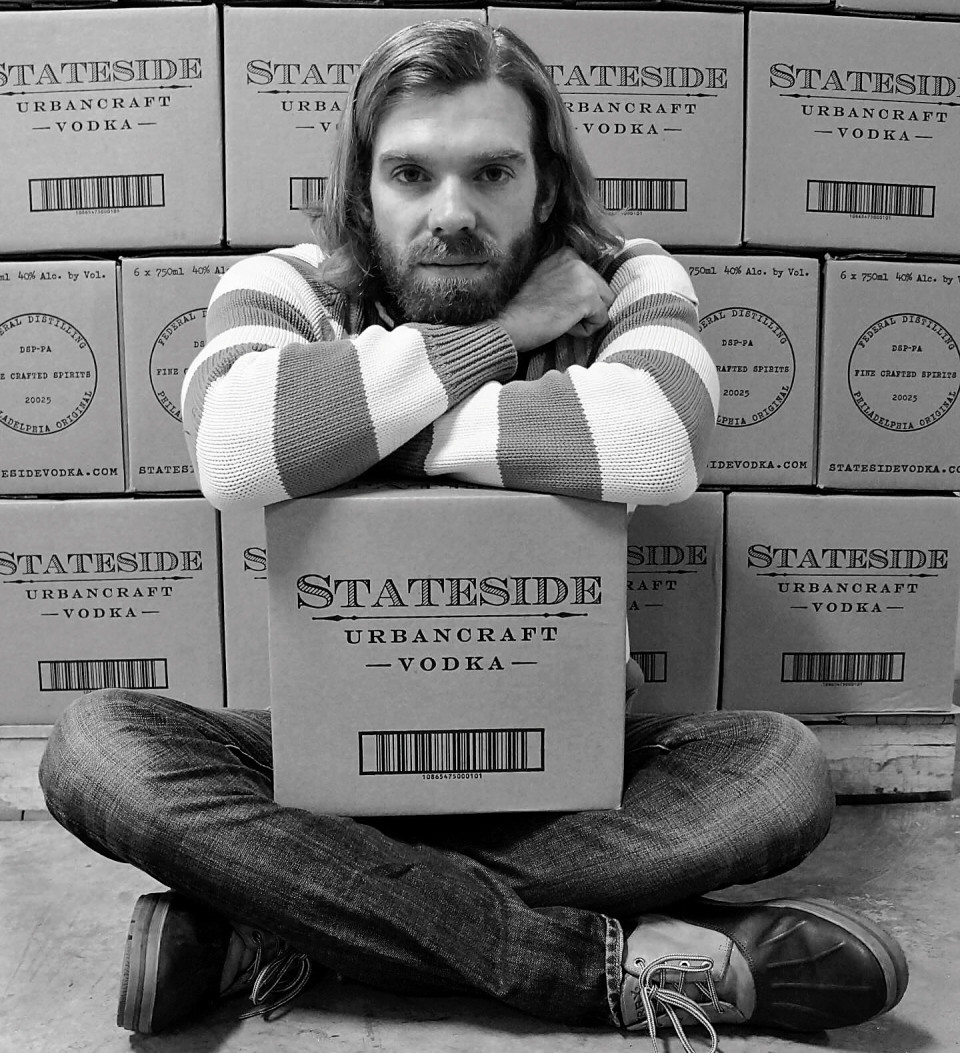

Surfside co-founder Matt Quigley in the early days of Stateside / Photograph courtesy of Stateside

“This is what I learned on,” he says. “This lived in the basement for a period of time, in a rinky-dink kind of distillation lab. And then my parents found it and were very unhappy with me.” It didn’t help that in 2013, everyone — including Quigley’s dad — was glued to the final season of Breaking Bad. “My dad seriously thought I was making meth in his basement.” The brothers were ordered to remove everything. Immediately.

Quigley shakes his head, puts the old piece of equipment back — it’s broken now, but he wants to weld it together again so it can be prominently displayed somewhere — and continues the tour. He points out the tiny area that used to house the boiler, back when this whole operation required far less horsepower; now the boiler room stretches across an entire wall. There’s the bottling line, where the vodka — distilled seven times — is piped through tubes that snake across the ceiling and into Stateside’s elegant glass bottles. (The canned products are manufactured in a dozen different production plants across the country; the alcohol is delivered to them in mega-tankers.)

This distillery and the vodka bar are staying put, Quigley tells me. They’re going to revisit the idea of building out a new distillery in a year or so. Things are fluid, because how do you predict the length and strength of a wildfire? You could look at White Claw, the malt-based alcoholic seltzer that supercharged the ready-to-drink cocktail category when it launched in 2016, becoming a cultural phenomenon that still dominates the market, doing nearly $2 billion in sales in 2023. You could also look at High Noon, the vodka-based hard seltzer that latched on to White Claw’s coattails in 2019 and was the top-selling alcohol brand by volume in 2023. You could look at Twisted Tea, Boston Beer Company’s beloved malt-based drink that still corners the market nearly 25 years after it launched.

But you could also look at Boston Beer’s other ready-to-drink cocktail, Truly, which made waves when it was introduced in 2016 but now is partly to blame for Boston Beer’s shipping volume and depletion decrease last year. In 2021, after overestimating the demand for these hard seltzers, the company had to destroy millions of cases of unsold Truly. You could go back further, to the Bacardi Breezer craze of the ’90s, the fluorescent wine coolers of the ’80s. Remember Zima?

But if Quigley is concerned about a possible downturn — the painful prospect of having to destroy unsold cases of Surfside one day — he doesn’t show it. He’s laser-focused, intense.

“We must win,” he says of the company. “We have to win. There’s no alternative.” In the bar, a neon sign hangs high overhead, a reminder of the stakes: BOOZE PAYS THE BILLS.

The day after his 40th birthday party, Clement Pappas, now 51, discovered a business plan in his bathroom. He didn’t know who’d sneaked it in, and he didn’t recognize the phone number on it. But he took a look anyway. Mason Jar, the company was called. Vodka, made in Philly, packaged in distinctly beautiful, antique-looking glass bottles.

“What really drew me to it more than anything was the image of the bottle,” Pappas says. He hadn’t been looking to get into the vodka business — he figured the market was crowded enough, and Pennsylvania’s liquor laws were archaic, especially back then, in 2014 — but his interest was piqued. The entrepreneur and would-be investor had been looking for a new project after his long-planned career trajectory in the family business was derailed. So he dialed the number.

Matt Quigley had been waiting for the call. It was his friend who had delivered the business plan, stealthily placing it where it would be found, hopefully read, maybe even considered. “He knew that I was looking for investors, and that I didn’t want a bullpen of 15 different people,” Quigley says. “He called me and said, ‘I have the perfect one for you. I’m going to his party. Get me a business plan and I’ll see what I can do.’ And so that’s how Clem and I met.”

Pappas remembers meeting with the Quigley brothers and trying the product. Between the three of them, they drank an entire bottle. “I thought it was the best vodka in America,” Pappas says. He wasn’t exaggerating — Quigley had honed his craft since being kicked out of the basement. He’d moved his equipment to his garage in South Philly, where he relentlessly studied the nuances of distilling. Eventually, he nabbed a coveted apprenticeship in Michigan State University’s artisan distilling program, a well-known launchpad in the spirits industry.

Pappas consulted with his good friend Eric Vesotsky, the managing partner of Mac’s Tavern in Old City. Vesotsky, whose partners in the tavern include local celebs Rob McElhenney and Kaitlin Olson of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia fame, had also seen the business plan.

“I don’t think anyone under the sun would have said, ‘Let’s start a vodka company or buy into one,’” Vesotsky says. “In Pennsylvania, the intricacies of selling alcohol are so strange, bordering on Utah. Travel a couple states south, and you can go to a gas station, fill up on unleaded, and grab anything you want from a bucket at the register. Here, we’re leaps and bounds in the other direction.”

Surfside’s owners, from left to right: Zach Pappas, Clement Pappas, Bryan Quigley, and Matt Quigley. / Photograph courtesy of Stateside

But if Pappas didn’t fully understand these regulations and red tape, he did know the beverage industry. He’d spent his whole life in the family business, Clement Pappas & Company, a fruit and vegetable cannery started in South Jersey in 1942 by his namesake grandfather, a Greek immigrant realizing the American dream. Eventually, as the canning supply-chain model evolved and Clement’s father and uncle took over, the company began producing fresh fruit juices for private labels.

It was always Pappas’s plan to run the business one day — after school (Duke; he later got his MBA at Wharton in ’09), and after working elsewhere first. (The Pappas rule: You had to work outside of the family business for a little while; Clement Pappas gamely worked as a business consultant in New York for a few years.) He came back to the juice company in 1999, overseeing manufacturing and then sales. Then, about a decade later, a string of unfortunate events: His father died; other family members decided to sell the business to a large Canadian juice entity; after some time, this entity wanted to take the business in a different direction; they all parted ways. And just like that, Clement Pappas, who’d always had his entire career mapped out — “I would hand this company down to my kids” — was out of a job.

Armed with his background in the beverage business and money from the juice company sale, Pappas decided he wanted in on the vodka. So did his brother, who came on as a silent investor. Seven months later, it was official: Clement was the CEO, Matt would handle manufacturing, and Bryan was in charge of sales.

The first order of business was changing the name.

“I don’t think we would have gotten anywhere if we had stayed with Mason Jar,” says Pappas. (He’s probably right. Can you imagine bellying up to a swanky bar and ordering a Mason Jar and club?)

“We wanted to say that we’re quality and American-made, but we didn’t want to put something out that was as cheesy as, like, Screamin’ Eagle vodka,” Quigley says. The team cycled through hundreds of options before landing on Stateside. They set their first deadline: the 2015 Whiskey Fest at the Linc, a festival featuring samples of hundreds of whiskeys and spirits, produced every year (coincidentally) by this magazine in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board.

“Working on something for over two and a half years and then watching the first person step up to the table and sample the product you made, and seeing their reaction? I was holding my breath, cowering in a corner a few yards away. I thought I was going to have a heart attack,” Quigley says. “When that first person was like, holy shit, this is really good, I just let out a sigh. Okay, cool. We’re out of the gate.”

They spent the next four years building up the brand bottle by bottle, doggedly chipping away at the local market before scaling up. And it was working; Stateside was becoming the local go-to vodka. They were distributed in three states and had more than 20 employees, plus a successful tasting room that accounted for 15 percent of their business. And then COVID hit, a small-business wrecking ball. Governor Tom Wolf shut down the state’s liquor stores, the only state to do so. Restaurants, bars, the tasting room — all closed.

Pappas, the numbers guy, looked at the books. “I go to Matt, ‘Listen, 88 percent of our revenue is mandated closed by the government. We have to lay off everybody, draw our credit line to the maximum, and hold on for dear life.’” Then the realization hit: The stills could still run. They could still produce the vodka. They could deliver.

“I imagine it was like what happened when Prohibition hit, except what we were doing was legal,” says Pappas. “All of a sudden, everybody was like, ‘I know a guy. I can get you the goods.’ We started blowing up.” They didn’t have an e-commerce platform, so they took orders by phone, set up a system for ID checking, slapped regulatory licenses on cars, and began delivering to the five-county area, plus Pittsburgh and places like Lancaster. At the height of it, they had 25 people ferrying their vodka around. By the end of April, their base volume had doubled, they’d brought back all of their employees, and they’d banked about a million dollars.

Stateside was back in business, this time with a war chest. The next logical question was this: What else is out there?

On the morning of the Eagles Super Bowl parade, Vicki Loo was with her team at KLG Public Relations, the New York-based firm that represents the Stateside and Surfside brands. It would be great, she mused, if they could somehow get content of fans at the parade shotgunning Surfside. (For the unenlightened, shotgunning is a way of quickly consuming a canned beverage, typically beer. You punch a hole near the bottom of the can, place your mouth over the hole, pull the tab, and chug. It’s not pretty.)

“Do you think you can even shotgun Surfsides?” she wondered aloud. “Or do you need the carbonation to make it work?”

And then, like a gift from the public-relations gods, a message from Russell Pareti, the CMO of Stateside brands, pinged in. It was a video of Jordan Davis, the Eagles defensive tackle, talking to a reporter at the parade. “Please enjoy responsibly, but we’re celebrating!” Davis says in the video. Grinning, he holds a can of Surfside up to the camera, its beachy, cheery stripes instantly recognizable.

“You shotgunning that? Do it, baby!” says the reporter.

“Everybody at Athens knows how it goes down,” Davis says, shouting out his alma mater, the University of Georgia, before he holds his mouth to the side of the can, cracks it open, and drains it in seconds. Marketing gold.

Even more virality was to come. As Mayor Cherelle Parker took to the Art Museum stage for her belabored five-minute address, the crowd chanted at her: “Spell it! Spell it! Spell it!” They were referring, of course, to Parker’s infamous press conference gaffe, in which she misspelled “Eagles.” As she wrapped up her speech at the parade, the crowd’s chants grew louder, no doubt buoyed by the plane flying overhead, towing a string of words attached to a colorful Surfside banner: WORLD CHAMPS E-L-G-S-E-S.

But the marketing wasn’t just in the sky. It was also underfoot, in the form of hundreds of empty Surfside cans crushed flat by the crowds, bright spots of color strewn along the streets. Quigley calls this “shrapnel,” and it’s partly what gave him the canned iced-tea-and-vodka idea in the first place.

“They don’t teach you this in business school, but if you really want to know what the people of your town or city are drinking, all you have to do is look at the ground,” he says. “You walk around Philadelphia and there’s a whole bunch of iced tea bottles and crushed iced tea cans all over the ground.” Wawa’s iced tea is iconic around these parts, as is Arctic Splash. (There’s an entire Instagram account devoted to the latter’s shrapnel, those instantly recognizable pint-sized cartons.) And of course there’s our city’s bizarre and long-standing obsession with Twisted Tea; Philadelphia is the top market for Twisted Tea Light globally.

Photograph via @robinsonalehouse

“With a fermented formulation and a stupid-simple saccharine flavor profile, you can grasp how firms big and small could have Mad-Libbed themselves into this piping-hot segment. What if Twisted Tea but less sugar? What if Twisted Tea but better flavor? What if Twisted Tea but in trendy slim cans?” Dave Infante wrote in a 2024 article for VinePair, a digital media company focused on drinking trends and culture. Brands like AriZona, Monster, and New Belgium tried, launching their own hard teas to middling success. But they’d all missed the gaping spirits-based hole in the ready-to-drink market.

“It’s not rocket science,” says Pappas. “How had nobody figured this out before? You’re not reinventing the wheel — it’s iced tea and lemonade and vodka.” But Surfside’s innovation was less about what was in the drink and more about what was left out: carbonation, for one, as opposed to the fizzy bloat of White Claw. And sugar, only two grams per 12 ounces, as compared to Twisted Tea’s 23 grams.

Stateside had already dipped into the ready-to-drink market with a launch of canned vodka sodas in 2021, an expansion made possible with that COVID war chest. The line was successful out of the gate, but Quigley wasn’t satisfied.

“I wanted something that was really unique to us, where we could say that we started this category. Everybody always wants to skate to where the puck is, but what you should be doing is skating to where the puck is going to end up,” Quigley says, referring to the oft-quoted line attributed to hockey legend Wayne Gretzky. The puck had been sliding toward low-sugar, no-carb options for a while, thanks to younger generations who don’t favor beer or bubbles. But it seemed like nobody was paying attention.

“We came to the conclusion that this RTD sector just didn’t exist,” says Quigley. “And if we didn’t do it, someone else would.” (Eventually.) The company was already overwhelmed with the demand for the vodka-soda drinks, but Quigley started working on the iced teas immediately, tinkering with formulations and branding. He mocked up graphics in Photoshop — colorful stripes wrapping around the bottom of the can; a bright yellow sun that, if you look closely, is actually a lemon sliced in half; a breezy sans serif font.

“I’m a lifelong surfer,” says Quigley. “We wanted to evoke this coastal vibe.” Though he has a buzz cut now, older photos show Quigley with long hair bleached by the sun and surf in Los Angeles, where he lived for a few years after graduating from Penn State.

Enjoying Surfsides in New Orleans / Photograph courtesy of David DeLuca

The working title for the boozy teas was Suncatcher, which they quickly scrapped so as not to rip off the name of the beloved Stone Harbor surf shop. At the time, Pappas was building a shore house in Avalon; the architect had dubbed the project “Surfside.” Pappas floated the name by Quigley, who instantly green-lit it. Surfside launched in early 2022 with 10,000 cases of iced tea and vodka, which sold out instantly. They doubled, then tripled, production, and quickly added three flavors to their flagship: lemonade, peach iced tea, and half iced tea, half lemonade.

“The advantage when you’re small is that you’re really nimble. You can change on a dime. And you can operate under the radar for a period of time before anybody even knows what the heck is going on,” says Quigley.

He’s right: No one in Big Beverage realized what this little distillery in Philly was doing until it was impossible to ignore: triple-digit growth in its second year, wildly expanding national distribution. Surfside hadn’t just skated to the puck and scored a goal. In terms of success in the canned cocktail market, they’d basically won the Stanley Cup.

Matt Quigley uses a lot of sports analogies when he talks about Surfside. It makes sense: Sports, especially in Philly, are what propelled the brand’s stratospheric growth in the first place.

Kevin Tedesco, the general manager of Aramark at Citizens Bank Park, remembers rolling Surfside out in the ballpark’s vending rooms, where hawkers — who work on commission — choose the products they’ll sell to fans in the seats. The ballpark had been pouring Stateside products for years; it wasn’t a hard sell to persuade the organization to take a chance on the newest offering. But they still hedged their bets.

“The first night, we sent about six cases to one of the vending rooms,” Tedesco says. “I think only one vendor carried it the first two nights.” A few games later, more vendors caught on, and before long, the cans were in nearly every vendor’s bucket, and Surfside was sending over pallets to restock the rooms.

It helped, of course, that the Phillies were good during that first Surfside summer. (It was 2022, when the team went to the World Series.)

“That’s a whole other dynamic to the stadium complex,” says Justin DeSalvo, the associate VP of operations for Live! Hospitality in the mid-Atlantic region, which includes Philly’s Xfinity Live! complex. “We have 40 to 45,000 people in Citizens Bank Park every night through the summer. Roughly eight million people come to the stadium complex on an annual basis. It was just one of those things. People saw Surfside in someone’s hand and so they tried it too, and it just spread like wildfire.”

“We always joke that when all the vendors want to carry it, you know it’s popular,” says Tedesco. But “popular” is underselling it: Surfside has been the top-selling spirits brand at Citizens Bank Park since 2023, eclipsing behemoths like Casamigos and Tito’s. And other ballparks have started to take notice.

“My baseball counterparts all over the country are calling me to ask about Surfside: ‘What’s their story?’” says Scott Nickle, the director of corporate sales for the Phillies. The story, Nickle tells them, is that the drinks, light and refreshing, are the perfect complement to a baseball game on a hot summer day. (Surfside, the modern-day Cracker Jack!) These counterparts are taking Nickle’s advice: As of this story’s publication, Surfside has partnerships with 11 MLB teams, eight NHL teams, two NBA teams, and one MLS club, plus Minor League Baseball.

“I’ve been in the industry for over 25 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this before,” DeSalvo says of Surfside’s meteoric growth. “They’ve captivated the market.” And inspired it: Since Surfside’s launch, big beverage conglomerates have hastily rolled out their own versions: Boston Beer Company’s Sun Cruiser, E. & J. Gallo’s hard tea version of High Noon, Anheuser-Busch’s recently released Skimmers. (“It has stripes on the bottom of the can, and a sun on the top,” Pappas says, pointedly. “And I don’t know if you’ve seen Sun Cruiser’s package, but I’ll note that it has multicolored stripes at the bottom.”)

Photograph by Kayla Adana

But while corporations play catch-up, that same puck is still sliding — only now it’s going in the opposite direction. Last year in the U.S., sales of booze-free beer and wine and zero-proof spirits grew by 26 percent, driven in part by millennials’ and Gen Zers’ embrace of no- to low-alcohol trends and a healthier lifestyle. Buzzy terms like “sober-curious” and “California sober” (definition: giving up alcohol and hard drugs but not marijuana) are leaping into the lexicon, and THC-infused products like edibles and elixirs are shuffling onto shelves. Hell, the surgeon general is calling for a health warning label on alcoholic beverages.

Once again, if Quigley and Pappas are concerned about all of this, they don’t show it. They’re focused on partnering with more colleges, especially those in the Midwest; their roster currently includes schools with high-profile sports teams, like the University of Alabama. There’s a trend, Pappas says, of college kids from the Northeast going to Southern schools. When they go, they take their fondness for Surfside with them, spreading it to Virginia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi — and also up north. Wildfire.

“We love Surfside,” says Hailey, a current student at Providence College in Rhode Island. “Most of my friends hate carbonation so that’s all they drink. The boys never drink High Noons or White Claws because they are ‘girly.’” The price point — $14.99 for a six-pack, notably higher than typical cheap college beers — isn’t a factor. (“I delivered pitas for Pita Pit for beer money when I was in college,” says Quigley. Today, Pappas notes, young adults have Venmo — “the ability to easily shuffle cash around a group of young friends” — and, increasingly, unbridled use of their parents’ credit cards.)

“Any trend ultimately falls off, but our point of view is now that Pandora’s box is open and we have these products out there, why would people go back?” Pappas says. (Reports have predicted that the ready-to-drink category will be worth more than $21 billion in the United States by 2027, making it the fastest-growing spirits sector.) Legislative currents are flowing in their favor too: Pennsylvania Act 86 of 2024, which went into effect this past September, finally — finally — allows ready-to-drink cocktails to be sold at licensed establishments like grocery stores and gas stations.

Surfside was prepared for all this extra shelf space: The brand has 12 flavors now; earlier this year, they unveiled new green tea options, more variety packs, and a new 700-milliliter size, called the Longboard. Surfside now makes up 80 percent of the company’s sales.

“We feel like we’ve been in the weight room for years and now we’re finally in the game,” says Quigley. “We want to show everyone what we’re capable of doing.” Surfside is on a national stage now, in ballparks and bars and beaches across the country. It’s in stadiums and at music festivals and on college campuses. It’s in the hands of Super Bowl champions.

But the Super Bowl happens every year. Plenty of teams have won the big game and then faded into the shadows. (Or, in the case of California Cooler and Zima and Four Loko and Truly iced tea, disappeared off shelves.) It’s hard to win once. It’s even harder to keep the streak going. Which is why Quigley excuses himself immediately after our distillery tour; he’s headed to New York for a dinner with people from the Islanders to celebrate a new partnership deal. Next week, he’s off to California to meet with more partners, the Kings and the Giants. The work doesn’t stop. Can’t stop.

After all, booze pays the bills.

Published as “Riding the Wave” in the May 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.